From Clive Davis The Times

From Clive Davis The Times

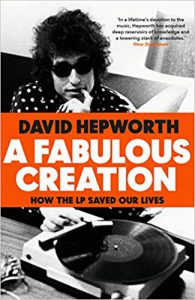

When reviewers say a book feels twice as long as it actually is, they are not usually being complimentary. In the case of David Hepworth’s paean to the age of vinyl, A Fabulous Creation, I really have come to praise him. It’s years since I came across a chronicle of the pop life containing so many arresting anecdotes that I found myself going back over pages to savour every line, every insight.

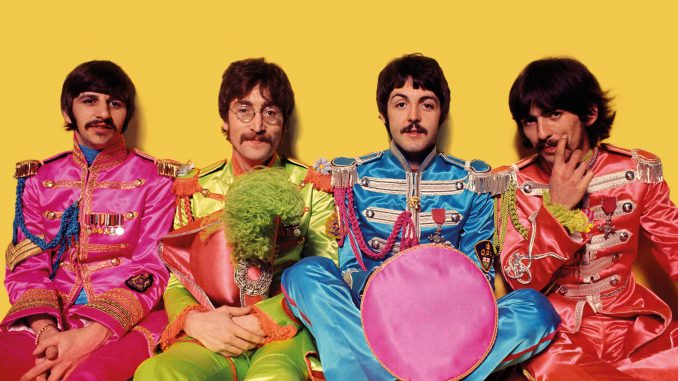

If you have read Hepworth’s earlier books, including 1971: Never a Dull Moment, his journey though the year he regards as rock’s annus mirabilis, you will know how entertaining a companion he can be. He is at our side again as he traces the evolution of the LP from Sgt Pepper in 1967 to the advent of the compact disc and MTV in the 1980s.

Hepworth came of age in this era, and so we keep catching glimpses of his younger selves, riffling through the vinyl racks at his favourite shops or watching his friends carrying out that most solemn of ritual: carefully lowering a stylus on to the grooves and waiting for the sounds to emerge from the hi-fi.

It was a time when people still liked to listen collectively. Now we use headphones to retreat into our own worlds. Recalling “our long march back into solitude”, Hepworth describes the first time he heard music on a Sony Walkman. In 1980 the Police’s drummer, Stewart Copeland, whom Hepworth was interviewing, had brought an early version of the Walkman back from a trip to Japan. Looking at the flimsy headphones, Hepworth was unprepared for the impact of hearing sound untethered from conventional equipment. A revolution was about to be unleashed.

Five years later the market for cassette sales had overtaken LPs, and the advent of the compact disc was changing our habits all over again. Pop videos, with ever more lavish budgets, were turning songs into an accessory to exotic visuals. Soon digital technology gave us the freedom to pick and choose our favourite tracks rather than accept them in the order that musicians and producers passed them down to us.

Today the LP is making a comeback of sorts, but Hepworth is too much of a realist to start swooning. For one thing, sales are tiny compared with the 1970s. More importantly, now that the internet has cast its spell over us, recalibrating our attention span and turning all of us into browsers, the way we listen has changed too. Since we have an infinity of music at our fingertips, albums no longer possess the same mystique.

As Hepworth puts it in a bittersweet valedictory chapter: “You can fill your room with the very best loudspeakers. You can spend your money on a pristine new copy of your favourite album. It can be produced on the highest quality vinyl. It can feel reassuringly weighty in your hand… The really difficult bit will be convincing yourself that for the next 40 minutes you have nothing better to do than listen to that record. Because that’s how it was back in the golden age of the LP. It seemed as though we had all the time in the world.”

10 memorable albums in David Hepworth’s record collection

- Bob Dylan: John Wesley Harding

“This may be my favourite Bob Dylan record. At the time it just seemed a bit dull. Where were the fireworks? Why no song about Vietnam? Now I realise it’s Dylan’s recalcitrance that has kept his career going this long.”

- Leonard Cohen: Songs of Leonard Cohen

“I’ve lived with the music of Leonard Cohen for 50 years. It took me 20 of those years to realise that, far from being miserable, he was often funny.”

- The Who: Who’s Next?

“I still insist that the most exciting bit of the most exciting track of the most exciting year in rock occurs around one minute six seconds into the first track here. Baba O’Riley is the Who in excelsis, which means it’s as powerful as rock gets.”

- Sly & the Family Stone: There’s A Riot Goin’ On

“Nearly 50 years later I still defy anyone not to find it the most challenging, edgy and provocative thing ever to get to the No 1 spot in the United States album market.”

- Joni Mitchell: Blue

“This record was like an x-ray, as she said afterwards. Nobody had ever done anything quite like it before.”

- Stevie Wonder: Talking Book

“This was the new version of Stevie Wonder. Newly grown-up and making the kind of records he felt like making.”

- The Wailers: Catch a Fire

“I can remember hearing this in one of those old-fashioned listening booths at a shop in Wood Green. Of course, what attracted everyone was the cover, which was specially fashioned, at ridiculous expense, to resemble a Zippo lighter.”

- Randy Newman: Good Old Boys

“I no longer dare play this record in my house for fear that it reaches the ears of anyone under the age of 40 who wouldn’t be able to hear beyond the language it uses… It’s the only concept album in rock that delivers.”

- David Bowie: Station to Station

“Cocaine has been responsible for some terrible records. It has also been responsible for some good ones. This still feels the way it felt at the time, as the harbinger of a new form of music which was mostly about the groove.”

- Fleetwood Mac: Tusk

“One of the things I’ve learnt while working on this book is that Fleetwood Mac are even better than I thought they were. Another thing I’ve learnt about albums is that when you grow tired of liking the obvious albums you can throw yourself into the arms of the not so obvious ones.”

LPs were around before Sgt Pepper, of course — an earlier generation had Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue or Frank Sinatra’s Songs for Swingin’ Lovers!. But this book focuses on how the Beatles, Bob Dylan and other musicians of the Sixties and Seventies used the long form to create their own version of art music. Pop records assumed the status of novels. Sleeve designs became almost as important as the sounds issuing from the microgrooves.

Hepworth adds an elegiac account of the process of buying an LP. He recalls the long, agonised shuffle through the new releases, the tense conversations with the oracles who stood on the other side of the shop counter. And he describes how, once you had made your purchase, you would carry this fragile object home, allowing the cover art to announce your good taste to the world at large. There was always a possibility of running into a stranger carrying the same album, in which case secret nods would be exchanged. To buy the right LP was to be inducted into a freemasonry.

Hepworth is an explorer returning from a lost world. Only a fraction of young people went to university; student loans lay far in the future, and there were always jobs to be found. In 1970 flats in areas of London such as Ray Davies’s old patch Muswell Hill were still cheap, and you could see the latest hip movie from Hollywood’s young rebels for about 30p. A new economy began to emerge to cater to the aspirations of youthful hedonists. The young Richard Branson, who was no music enthusiast — he apparently did not even own a record player — realised there was money to be made by selling records by mail order. Across the Atlantic in New York, Columbia Records, famous as the home of Glenn Gould and Barbra Streisand, shifted its attention to Santana and Blood, Sweat & Tears.

Hepworth evokes the idealism and grubbiness of the times. Having spent so many years covering the industry, he has an intimate grasp of how great music can be the result of grand notions of personal liberation, or merely the pursuit of the mighty dollar. Or both. Most bands may only have a few ideas in them; they end up carrying on for decades because “the kids need new shoes”. Bills have to be paid. We get a glimpse of Janis Joplin rehearsing for her producer: “This is my Tina Turner scream. This is my Big Mama Thornton scream. Which one shall I use in this spot?”

Hepworth is not afraid of making disrespectful noises about other legends too. He can be lukewarm about Patti Smith and Oasis, and in the fascinating digression into comedy albums he shakes his head over the cult status of Peter Cook and Dudley Moore’s Derek and Clive double act. Above all, he is wise enough not to wallow in nostalgia for the passing of the LP. His mother was quite content to use cassettes because they were much more durable, and if Hepworth still clings on to his vinyl, he understands why the next generation doesn’t see the mystique. If they read this book, though, they will start to see what they are missing.A Fabulous Creation: How the LP Saved Our Lives by David Hepworth, Bantam, 368pp,

Find all the vinyl you’ve been missing here at eil.com

eil.com – the world’s best online store for rare, collectable and out of print Vinyl Records, CDs & Music memorabilia since 1987

Be the first to comment