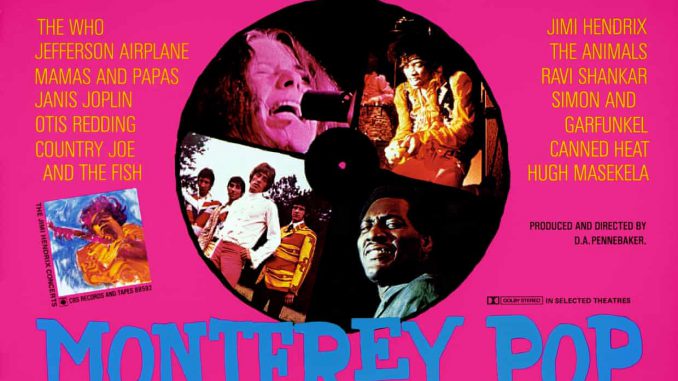

In a final, previously unpublished Guardian interview, the late great documentarian looks back at his groundbreaking film with Lou Adler, the legendary music festival’s promoter.

Lou Adler, promoter and producer

In 1967 there was a meeting at Mama Cass’s house that included Paul McCartney. The general conversation was: “Why isn’t rock’n’roll considered an art form in the way that jazz and folk are?” A few weeks later, the promoters Alan Pariser and Ben Shapiro got in touch to book the Mamas and the Papas for one night at Monterey County Fairgrounds in California. We said we’d think about it. About three o’clock in the morning I got a call from John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas. He said: “Why don’t we do a festival, add more days, and get the acts to play for nothing?” This was a chance to elevate how rock’n’roll was thought of.

We had six weeks. Without Chip Monck I don’t know if we would still be talking about Monterey Pop festival. He had to build the stage, put in all the lights and sound, and get 35 acts on and off. That had never happened before. We wanted to show all the genres of rock’n’roll: the blues people, the San Francisco groups, the groups from England. We tried for all the Motown acts but I don’t know that [label founder] Berry Gordy understood what we were doing. You had to really buy into it if your acts weren’t going to get paid.

During the festival I was either backstage, right on the stage, or saving instruments in the case of the Who and Hendrix. It was pretty phenomenal. Otis Redding was beyond anything I had ever seen. That was the largest white crowd he had ever performed for. And Hendrix, of course. A couple of girls in the movie look like they could be watching a horror film – they don’t know what they’re seeing.

It was the last time you would see so many performers in an audience. Most of these acts had heard about the others but had never seen them so they were as curious as anybody. Woodstock was about the weather and the number of people; Monterey was about the music. That’s the difference.

We made a deal with ABC to do a movie for television. We asked DA Pennebaker because of [Dylan concert tour doc] Don’t Look Back. He really understands the music and the personalities. Once we looked at the footage, Pennebaker said: “This is not a television show. This is a movie.” But we went to see Tom Moore, the head of ABC and a very conservative southern gentleman, and showed him Jimi Hendrix [humping] his amp. He said, “Not on my network,” and gave it back to us. We knew exactly what we were doing.

With the advent of FM radio, Rolling Stone magazine and the festival, rock’n’roll was truly elevated. Promoters realised they could do festivals, which eventually grew into [the likes of] Coachella. It’s unfortunate how many people who performed at Monterey are no longer with us, but they’re with us because of Pennebaker. I play the film at universities and when Hendrix and Otis and Joplin finish I hear applause – these people are there.

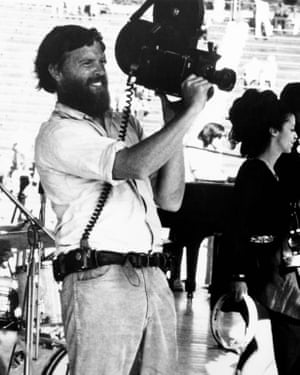

DA Pennebaker, director

John Phillips asked if I’d be interested in doing a film of a music festival in Monterey, California. Generally people from Los Angeles and people from San Francisco had conflicting musical tastes. Monterey was a way of joining the state where it hadn’t been joined before. What made it successful was the decision to throw the big-money ideas out of the window. People really came to play and hear each other play. They weren’t there to make money.

I made Don’t Look Back by myself but Monterey Pop was made by the people who worked with me. I didn’t direct it really – I edited it, but they all saw it differently and filmed it how they saw it. They were learning to make films right there in front of me. We only had a limited amount of film so we decided on a particular song for each group, but in fact people shot anything that interested them and we had to go down to Los Angeles twice to get more film stock.

I liked the idea of watching music expand its possibilities as it went along: the movie started with Canned Heat doing a simple country song, and ended with Ravi Shankar playing really complicated work. Music was moving so fast and nobody understood what was coming next. I grew up loving jazz. At Monterey I could see that the music of my youth was no longer what was going on.

We came back to New York with so much footage we had to get people in to help us. We went three or four days straight, 24 hours a day, screening all the rushes, and everybody came to see them, including Shankar. I dozed and woke up and dozed and woke up so when I sat down to edit it, it felt like a wonderful dream.

• The Complete Monterey Pop Festival is out now on Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Dorian Lynskey at the Guardian

eil.com – the world’s best online store for rare, collectable and out of print Vinyl Records, CDs & Music memorabilia since 1987

Be the first to comment