It’s 50 years since Paul McCartney came up with Hey Jude while driving from London to Surrey – and made a song that’s sung everywhere from football terraces to Oxford colleges. Here’s the story of how it came to be.

You could argue forever about which of the Beatles’ songs is the greatest. According to the Daily Telegraph, it’s something nostalgic: In My Life. According to the NME, it’s something psychedelic: Strawberry Fields Forever, which wasn’t even the best song on the single it appeared on, alongside Penny Lane. According to Rolling Stone and USA Today, it’s something epic: A Day in the Life, which often does well in polls, perhaps because it’s written by both Lennon and McCartney.

The debate is diverting but doomed. The Beatles’ range was so broad that it would be easier to name Matisse’s best painting or Meryl Streep’s best performance – which wouldn’t be easy at all. This isn’t just apples and oranges, it’s the whole fruit stall, so if we must use superlatives, we’d better narrow them down. The most covered Beatles song is Yesterday, the biggest seller is She Loves You and the biggest crowdpleaser is Hey Jude.

Hey Jude, which turns 50 on 30 August, is the Beatles song most likely to be bellowed by a choir of thousands. At Manchester City, fans sang it after the team won their first Premier League title in 2012. At Arsenal, Gooners used it to serenade Olivier Giroud, the team’s sleek French striker, who said of the track before he left for Chelsea : “It gives me goosebumps.” It also rings out at Newcastle and Cardiff, thus spanning the four points of the Premier League compass. Any decent song needs to be singable, but Hey Jude goes further: it’s yellable and flexible. Into the gap after “Nahh, na, na, nahh-na-na, nahhh”, you can slot almost any pair of syllables – Giroud, City, Geordie.

The song has also become a cricket chant. England supporters sing it for Joe Root, the team’s boyish captain. And it has been sung for the rain – at Edgbaston last year, when a shower sent England and Australia off the field. “The only good thing that came out of [the match],” said Shane Warne, commentating on Sky, “was the crowd’s wonderful rendition of Hey Jude.”

Those nahh-nahs know no class boundaries. At Westminster School, at which fees cost more than £23,000 a year, the boys and girls went into Latin prayers one day in 2012 and pulled a stunt planned on Facebook, singing Hey Jude as the organist launched into Deus Misereatur. Contacted by the London Evening Standard, the headteacher kept his cool. “Their Hey Jude stopped after the first verse because I don’t think they knew any more of the words,” Stephen Spurr said. “I felt tempted to sing them.” At Oxford in 2016, the matriculation ceremony that welcomes every undergraduate was enlivened by a group of students deciding that what the Sheldonian Theatre needed, on a Saturday morning, was a drunken rendition of Hey Jude. So they walked into the building, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, wearing gowns and mortarboards and belted out the Beatles classic.

Hey Jude is a crowd-pleaser in another sense. On Christmas Eve 2015, the Beatles’ music appeared, belatedly, on streaming sites: like the Queen going to a party, McCartney and Ringo Starr prefer to arrive after everyone else. For the Beatles obsessive, Christmas had come a day early – all the songs on tap, plus a popularity contest. A little chart was published, with Hey Jude joining Come Together and Let It Be on the podium. Though the Beatles’ early hits sold more copies, it’s the later ones that linger. And our tastes are fairly settled now. This month, Hey Jude was the No 1 Beatles song on Apple Music; on Spotify, it was No 4, again just behind Let It Be and Come Together, with the George Harrison-penned Here Comes the Sun pipping them all (despite not being a single – go, George!). So, of all the countless classics the Beatles recorded, Hey Jude is one of the three or four that younger music lovers most want to hear. What is its secret?

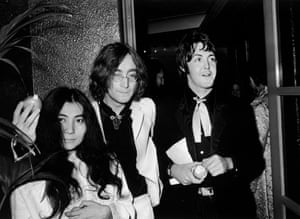

The tune and the germ of the lyrics came to McCartney in June 1968, when he was driving from London to Weybridge in Surrey to see Cynthia and Julian Lennon after John had left them for Yoko Ono. Hey Jude began as Hey Jules, an arm round the shoulder of a five-year-old, so the compassion was there all along. McCartney was good at playing with Julian, whereas Lennon, by his own admission, did not know how to. In a photo from this period, McCartney is seen holding Julian, looking paternal, while Lennon remains in the background, looking like a rock star.

The fact that McCartney was at the wheel, not doodling on the piano or the guitar, when he wrote the song forced him to keep it simple. It nudged him towards the sort of composition – inclusive, communal, family friendly – that sounds perfect in a group setting.

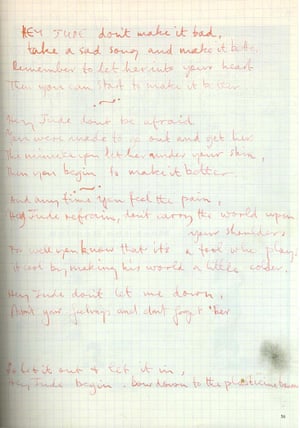

Back in London, he recorded some demos on the piano. These roots, too, would remain visible: the finished Hey Jude begins as a piano ballad, performed solo for 25 seconds, before building into something more ambitious. As McCartney sang by himself, the words evolved. Asked why he had changed Jules to Jude, he came out with the songwriter’s all-purpose answer: “because it sounded better”. Perhaps he also wanted to protect Julian’s privacy, or perhaps the reassurance was now pointed at a man in a romantic quandary:

Hey Jude, don’t be afraid

You were made to go out and get her

The minute you let her under your skin

Then you begin to make it better

The facts, for what they are worth, support McCartney. Lennon was living with Ono, at Starr’s flat at 34 Montagu Square in west London; the stucco facade now wears a blue plaque to that effect. Romantically, McCartney was on a similar path, less painful – no marriage to dissolve, no child to dismay – but more entangled. He had been dumped by his fiancee, Jane Asher, after being caught in bed with Francie Schwartz, was secretly dating Maggie McGivern and had just fallen for his future wife, Linda Eastman. One day, all this will be a biopic.

By then, Lennon and McCartney were writing separately, but still acting as each other’s sounding board. After working on Hey Jude some more, McCartney invited Lennon and Ono to his house in north-west London and played it to them. One line, “The movement you need is on your shoulder”, was there as a placeholder. “I’ll change that,” McCartney said. “It’s a bit crummy.” “You won’t, you know,” Lennon replied. “That’s the best line in it.”

This exchange, recounted by McCartney in 1994, had two consequences, beyond preserving the line. “You love it twice as much,” he said, “because it’s a little mutt that you were about to put down.” And it would forever remind him of Lennon: “That is when I think of John, when I hear myself singing that line. It’s an emotional point in the song.”

The weak link in the lyrics was elsewhere, right at the top: “Hey Jude, don’t make it bad / Take a sad song and make it better.” This doesn’t make sense, because a sad song is not a bad thing, as McCartney, of all people, knows. But in music, meaning doesn’t always mean very much. These were the first words that came to him in the car and they stayed. They have redeeming features – they are immediate, they are conversational and they get the rhyme scheme going (an artful AABBCCB). They are, however, just not as good as the next bit: “Remember, to let her into your heart / Then you can start to make it better.”

The heart is standard stuff in pop lyrics, but McCartney breathes life into it by making it one of only three images in Hey Jude, all parts of the body – “into your heart”, “under your skin”, “on your shoulder” – and all at the end of a line. They make the song more touching.

At this stage, Hey Jude was still a piano ballad. It could have become a classic in that form, but McCartney had other plans. One side of his personality, the cuddly uncle, had started the song; the other side, the ruthless artist, had now taken over. McCartney wanted Hey Jude to be long (it ended up just over seven minutes, three times the length of the Beatles’ early hits). He also wanted the ballad to swell into a riff and the fade-out to end all fade-outs.

The Beatles’ producer, George Martin, protested that seven minutes was too long and radio DJs would not play the record. Lennon said: “They will if it’s us.” It was arrogant but accurate.

Martin conceded the point (“I was shouted down by the boys, not for the first time in my life”) and came up with a plan of his own. “I realised that by putting an orchestra on, you could add lots of weight to the riff by [having] counter-chords on the bottom end and bringing in trombones and strings, until it became a really big tumultuous thing.”

When Harrison offered a guitar solo to form a call-and-response with the nahh-nas, McCartney flatly refused. “Paul had fixed an idea in his brain as to how to record one of his songs,” Harrison said. “He wasn’t open to anybody else’s suggestions.”

Martin and Lennon had found otherwise, but McCartney pleaded half-guilty. “Looking back on it,” he said in 1994, “I think, OK, well, it was bossy. But it was ballsy, because I could have bowed to the pressure.”

The Beatles recorded the first half of Hey Jude at Abbey Road on 29–30 July 1968, keeping their usual hours: 7.30pm or 8.30pm till three or four in the morning. They all played together: McCartney on piano, Harrison on electric guitar, Lennon on acoustic and Starr on drums and tambourine.

The next day they moved to another studio – Trident in Soho, central London, which had eight-track recording – to do the second half. They were joined by 36 classical musicians (credited only by instrument: “one bassoon, one contrabassoon…”), arranged by Martin, who, unlike McCartney, could read music. The cast of Hey Jude had gone from one to 40, like a chart run-down in reverse.

After playing, the orchestra were offered double pay to add handclaps and sing the nahh-nas. This prompted another rebuke, this time from one of their number. “I’m not going to clap my hands,” they reportedly said, “and sing Paul McCartney’s bloody song!”

A week earlier, with Helter Skelter, McCartney had made a racket that would be hailed as both proto-metal and proto-punk. Now, with Hey Jude, he pioneered the stadium-rock singalong, even though the Beatles had quit touring two years earlier.

Hey Jude became an instant classic. It spent nine weeks at No 1 in the US, the Beatles’ personal best. By the end of the 60s, it had been recorded by Elvis Presley, Smokey Robinson, Diana Ross and Ella Fitzgerald. At McCartney’s gigs, it often has pride of place as the last track before the encore. When he played at the ICA in London in 2007, McCartney left the stage, the crowd kept up the nahh-nas, and, on his return, he and the band joined in, in a lovely little reversal.

Hey Jude may seldom top the polls, but it drew the highest praise from one judge. “That’s Paul’s best song,” Lennon once said.

****

If you’re looking for copies of Hey Jude, explore what eil.com has in stock. New arrivals daily from The Beatles, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, John Lennon & Ringo Starr.

eil.com – the world’s best online store for rare, collectable and out of print Vinyl Records, CDs & Music memorabilia since 1987

Love the BEATLES history lesson of “Hey Jude” in the above. Very nice article by you mob.