First record? It’s the most standard of questions – one that any respondent, be they pop star or punter, can answer without hesitation. For almost anyone born before 1980, that very first walk up to the record shop counter will have involved the purchase of a seven-inch single. From the moment you walk out of the shop, carrier bag in hand, it’s a matter of getting home in a state of ever-heightening anticipation. In a pre-Spotify, pre-everything-on-demand era, that was the power that music had. In our house, we had a radiogram, a free standing teak unit with speakers and a tuning dial at the front with a lid on top which, when opened, would reveal a turntable. In the posh room at the back that hardly ever got used, our radiogram was the focal point. And it was on this that I played my maiden purchase: The Barron Knights’ ‘A Taste Of Aggro’. The Barron Knights were a comedy group whose calling-card was three-song medleys which would typically be comprised of recent hits, all with their lyrics rewritten so that nine year-olds like me found them funny. ‘A Taste Of Aggro’ began with an interpolation of ‘Rivers Of Babylon’, which went, “There’s a dentist in Birmingham/He fixed my crown/And while I slept/He filled my mouth with iron.” I listened to that record again and again and again, and then when I could listen to it no more, I did what any other child with a collection totalling one record would do. I played the B-side.

The B-side of ‘A Taste Of Aggro’ was pretty strange. Called ‘Remember/Decimalization,’ this reflective paean to pre-metric times didn’t appear to have any jokes in it. But then, perhaps it was one big gag? After all, how could anyone write such a soulful testimonial to an outmoded currency? Was this a Vivian Stanshall-style flight of bittersweet whimsy? A failed experiment? I didn’t know then – and I still don’t know, because, of course, what I’ve since come to realise is that B-sides can be all or any of these things. The more you think about the idea of the B-side, the more fascinating it becomes. A B-side is, in one sense, a by-product. A quirk of the format on which it features. Its passage into the world is a precise inversion of the A-side’s journey here. An A-side is a song whose appeal is so great that it’s deemed worth an expense of hundreds, perhaps thousands of pounds, involving studios, pressing plants and artwork. All of this happens because someone wrote a song so good that it was deemed worthy of having an artefact manufactured that would house it exclusively. And once all of that is done, the next thing that requires attention is the B-side. The B-side is both a problem and a solution to a problem. When an empty space needs to be filled with something, something creative can happen.

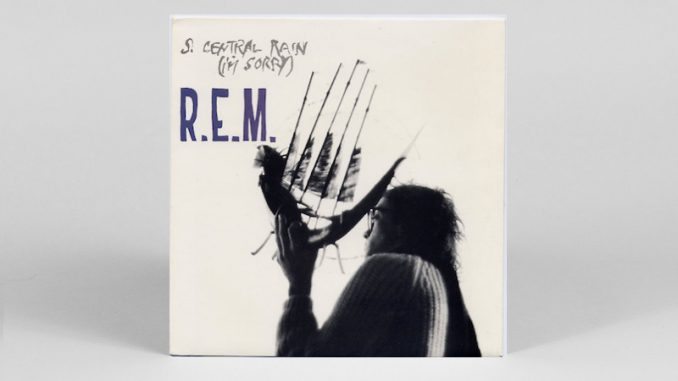

But that depends, of course, on what your attitude to that blank space is. The least interesting (and most common sort of) B-sides are the B-sides which act as mere repositories for songs that weren’t good enough to make it onto an album. So what other ways of approaching a B-side are there? In the liner notes to Dead Letter Office, REM’s Peter Buck is admirably forthright: “A 45 is still essentially a piece of crap usually purchased by teenagers. This is why musicians feel free to put just about anything on the B-side; nobody will listen to it anyway, so why not have some fun?” Once in a while though, this laissez-faire attitude results in moments of pop gold. Included on the B-side of REM’s 1984 single ‘So. Central Rain’ is ‘The Voice Of Harold.’ Here, an audibly soused Michael Stipe improvises a lyric from the liner notes of an old gospel album.

Often this can be the most rewarding sort of B-side: an idea so off-kilter that the band simply can’t get a handle on its commercial viability. In the wake of Wings’ dissolution, Paul McCartney’s McCartney II was an exercise in electronic introspective intimacy, greeted with ambivalence at the time by journalists who had forgotten that Paul had always been the most experimentally minded of all the Beatles. Album tracks such as ‘Frozen Jap’ and ‘Temporary Secretary’ were decades ahead of their time, but even Macca didn’t quite know what to do with ‘Check My Machine,’ an indescribable collision of mutant Macca vocals interweaving over a thoroughly catchy mid-tempo groover. More than anything else in Sir Paul’s oeuvre, this is the song that Macca-obsessed Alexis Taylor of Hot Chip cites as his favourite.

Read the full article here at Vinyl Factory.

Be the first to comment