To mark the publication of a pictorial history of the songwriters Mike Stock talks about the ‘Hit Factory’ years.

Mike Stock interviewed by Tim Jonze at The Guardian – read the original article here

When I look back on the peak days of Stock, Aitken and Waterman, it’s all a bit of a blur. I wish we’d been able to stop and pace ourselves, but when people are knocking on your door, saying: “We need a record by tomorrow,” you don’t have time for a break. And you don’t want to let anyone down. That was the pressure we were under and, looking back, I don’t know how I did it.

We didn’t just write the songs – Matt Aitken and I were the band. We played drums, guitars, pianos, did string arrangements, everything. A lot of people don’t realise that we were actually the band, and therefore the most successful band there’s ever been. Just don’t tell Paul McCartney that.

There was obviously a spark between the three of us when we started working together. Pete was very sparky on the business side and Matt and I had all sorts of ideas buzzing around.

Our first success was The Upstroke by Agents Aren’t Aeroplanes, which we conceived as a female version of Frankie Goes to Hollywood. We’d been introduced to what was known then as boystown – an early incarnation of Hi-NRG that was played on the underground gay music scene in London.

Most of the records people were getting excited about were cheaply made American imports where the song was less important, and we thought that was an area where Matt and I could really add to the equation. Barry Evangeli, who ran a small label out of Camden called Proto Records, which specialised in the gay music scene, came to our studio on one occasion and told us the most important thing: to make sure the bass drum nails the beat to the floor and punches a hole in the wall.

I didn’t go to the clubs. I once went to Bang and felt out of place. They were all on stuff, the uppers and the poppers and whatever they were taking, and I was just observing. It was all going off, but I wasn’t going off with it.

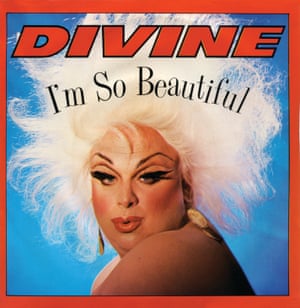

We worked with some characters in those early days. Divine and Pete Burns were exactly as you’d imagine from their videos and interviews. They had reputations based on outrageous behaviour and carried this through into their lives. I never saw Pete Burns without full makeup. I did see Divine in a cardigan and a pair of slacks, though.

Pete had an acid tongue and I felt a few of those barbs on occasion. But he was a nice bloke when you got to know him. He was in love with music and dance and would get childishly excited about a chord change. He’d say “What was that chord, Mike?” and I’d say “It’s an F sharp” and he’d make a note of it, saying he wanted to use it again. It was a bit strange, he didn’t really understand how it worked, but he was very excited by it.

Even after we had a No 1 with Dead Or Alive’s You Spin Me Round (Like a Record) in March 1985, there was no money coming in for a good 18 months. I don’t want to plead poverty, but we were struggling back then, living on nothing. If I had £2 in my pocket to go and buy a sandwich that was about it. Any money we did make was fed straight back into forming our own studio, equipping it and getting a team around us. It was hand to mouth but we were so fixed on where we were going we got carried along by the excitement of it all.

I was excited to work with Donna Summer simply because of her superb vocal ability. I really regret we never made a second album with her. At the time we worked with her, in 1989, she’d made a few inappropriate comments [Summer was quoted as saying “I have seen the evils of homosexuality; Aids is the result of your sins”, which alienated her large gay fanbase, although she later denied the quote]. And she was also ashamed of some of her past recordings in the 70s – because she was singing in a vertical position about what she was imagining doing horizontally. She told me she hated the idea of telling her kids about them. So we were a good fit because as a songwriter I’m a purist – I would never use a swearword or phrase that date-stamps your music. I’m always trying to write a classic, so if it gets date-stamped, you’re in trouble.

She had a magic to her that few artists have. I’d sing her my song, she’d learn it, then she’d sing it back with whistles and bells and all sorts of things going on. She had that skill and feel for music. With other singers it was harder work. They’d sing the tune back to you and it wasn’t even as good as when you’d sung it!

There’s more to being a pop star than being able to sing. Donna was a good singer, but she wasn’t a pretty little girl who flounced around dancing. There are people who can be dancers, movers and be attractive personalities singing little pop songs, which is just as valid as a great diva belting out some monster track. We didn’t pick up Jason Donovanbecause of his vocal ability – that was unknown to me at the time. He wasn’t Pavarotti, but we didn’t want that from him.

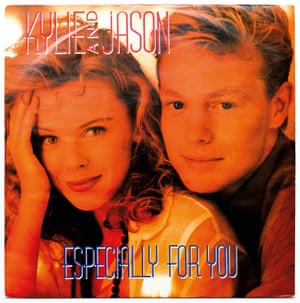

Kylie Minogue was the complete package, though. A great little singer, a great-looking girl, a great little dancer. Unfortunately, we’d insulted her when we recorded I Should Be So Lucky: she’d been hanging around all week and Pete forgot to tell us. We had to get the song together in about 40 minutes and she left not having had a happy experience. We didn’t know we had a hit on our hands and so when it went to No 1 for five weeks, someone said: “What’s the follow-up?” We didn’t have one. So I went out to Australia at the start of 1988 and met her in a bar with Jason and her manager. I basically crawled 100 yards on my knees and apologised profusely. She took it well and we did some more recording. She would be working on Neighbours from 5am, then come to record with me at 6pm. Tiring for her. But at least this time I had the songs ready, the lyrics typed up and everything in order.

I said to Matt when we started working with her that it would be our purple patch because all the signs were right – they were just moving Neighbours from before the lunchtime news on a Wednesday to every day before the evening news. So we had an advert for her on the BBC every single day. I put all my effort into her.

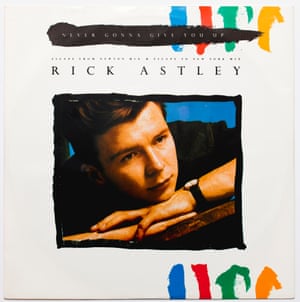

Despite what happened with I Should Be So Lucky, it’s a myth that we wrote things so quickly. Pete said Never Gonna Give You Up took three minutes? Well he’s lying. And what would he know, anyway? Pete loves a good headline. He once said he’d written Too Many Broken Hearts with Jason while he was sitting on the toilet. Now, that’s not a good image.

Anyway, for Rick Astley’s song I didn’t want it to sound like Kylie or Bananarama so I looked at the Colonel Abrams track Trapped and recreated that syncopated bassline in a way that suited our song. It gave it the extra dimension that made it successful. But it all took a couple of months to get there – not constantly, because we’d always have lots of songs on the back burner and work on different ones throughout the day.

I think the peak of the madness was when Woolworths said they had orders for the Kylie and Jason duet for Christmas and asked when we could deliver. We hadn’t even thought about it. I didn’t want to do it because of the Walt Disney thing – you never saw Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck on the same poster because you don’t confuse your brands. But I felt if so many people were asking about it, then that was a vote of confidence from the public, so I had to really live up to it with a song that justified their belief. That’s where Especially for You came from.

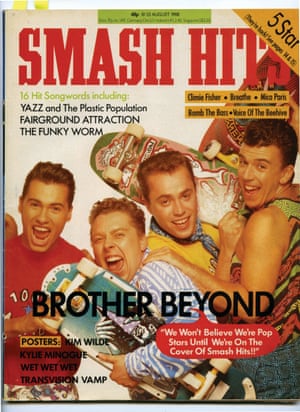

We were writing songs for the bright young things and that suited Smash Hits. They realised that if they put Kylie on the cover they could sell another 200,000 copies, whereas if they put some big black American diva on it you might not – that might sound like a racist comment, but it’s just what I heard at the time about how it worked. Serious, credible artists didn’t sell issues of Smash Hits, whereas Big Fun or Jason Donovan would work.

We were closely associated with the 80s, but we were never political. You can look back at the times and draw comparisons with Thatcherism, but I don’t even know how Matt voted – we never discussed party politics. But while there was no conscious decision, I do believe there was a feeling that freedoms were growing, that there was more disposable cash around in the 80s. I remember the late 70s: one week there was a shortage of sugar, one week it was toilet paper. The streets were full of rubbish when the binmen went on strike. Then there was the three-day week, and electricity cuts at 4pm because the grid couldn’t cope. So when Margaret Thatcher took over, there was a feeling that things were going to get better. Maybe we took advantage of that feeling, but we certainly didn’t have any connections with politicians or parties.

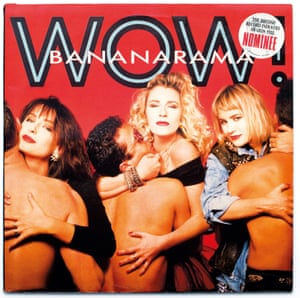

There was never any respect for what we did. We went to the Royal Albert Hall one evening for an awards show – we were being awarded something for a dance mix of one of Bananarama’s hits. But that wasn’t credible enough for all the DJs in the audience with their funny hats and whistles, so they pelted us when we went on stage to collect it. I got a can of urine that hit me on the shoulder. We beat a hasty retreat to a pub, where Pete was ready to explode because he was a DJ back in the day and didn’t like the thought that the people he had the most connection with were being so derisive, when all we’d done was make decent records.

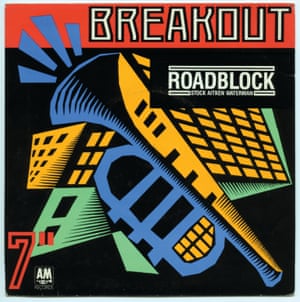

We were getting reviewed at the time by people who shouldn’t have been reviewing us. One paper was Black Echoes, which was more of an underground paper, but they would review Bananarama just so they could say it was crap. So I put Roadblock together on a Friday afternoon and put it out without telling anyone who it was. I’d learned all kinds of different styles and played disco in the 70s, so it was wrong for people to think we could only do Kylie and Bananarama records. Anyway, one of the first papers to review it was Black Echoes, which said it was the best goddamn dance record of 1987. That was before they knew it was us. We weren’t trying to fool the public, we were trying to fool the critics. And we did it! Even Bananarama said, “This sounds like a 70s groove, you could never do something like that.”

It’s a myth about how awkward Bananarama were, but they were a bit feisty. The biggest problem was when you were sitting opposite them and trying to write a song. Paul Gambaccini once said at the Ivor Novello awards that writing songs was one of the two most intimate things you could do with another person. It’s true. Matt and I had a relationship going where it was all right if I sang a silly tune and made a funny noise out my mouth – ooh ahh ooh, or whatever. You didn’t feel embarrassed because it was part of the process. But in front of Bananarama it became excruciatingly, painfully embarrassing. They’d laugh at you and mock you, when all you were trying to do was create a song for them. But I’m not knocking them as artists, because they were splendid artists – and they were good company in the pub, too.

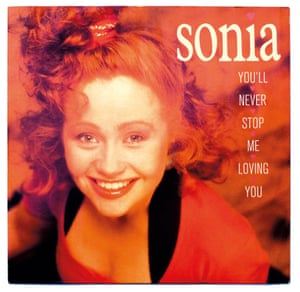

Looking back, I’d say Sonia’s You’ll Never Stop Me Loving You was one of my proudest No 1s. She was a completely unknown singer who had approached Pete, so the public didn’t know her – she was a blank canvas. I had to sit down and think what I could write for her that would be believable. The same thing happened with Mel and Kim and Respectable. They were unknowns, so it was a bit source of pride when they went to No 1.

After the poll tax riots in 1990, the flavour of Britain changed. The music went into acid house and became quite dark. Bright pop was no longer on the menu, and this coincided with Matt leaving our triumvirate. I would pick up anything I could to try and give us a hit. We did a Viz record, although I have no idea why we did that. But I never have the view that something is beneath us. We also did the WWF record [Slam Jam by the WWF Superstars] with Simon Cowell, which was only a novelty if you didn’t like WWF, because there were some very passionate people around that: 12-year-old boys loved it.

The main problem around this time was within ourselves. We set up Stock, Aitken, Waterman as our own thing, but Pete ended up selling the family silver [Waterman sold 50% of his label, PWL, which released the SAW records, to Warner Music in 1992]. In our last year, 1993, I had 50 or 60 songs and only got two records out. One day Pete walked into the office, whooping and hollering because he got a salary cheque. That was the end for me, because I only got paid if we had a hit record, and if the label isn’t putting out the records, then you’re not getting a hit. That destroyed the relationship, really.

We’ve been reappraised recently, but I’m not that bothered about respect. I don’t want to sound arrogant, but I really don’t care what people think about me. As long as I’m true to myself and believe in what I’m doing, that’s all that’s important. What people are saying now are things we already knew – that the songs are more complex than people think, the structures are more difficult than they imagine, the musicality is deeper. The overall impression is the songs are simple, but it’s a studied simplicity. I’d challenge anyone to pick up a guitar or sit at a piano and try and work out what we did – it wasn’t easy.

Find all these artists and more in stock on 12″ single, 7″ single, rare and out of print vinyl and CDs at eil.com

Got an article for our blog? Contact Tim: tim.card@eil.com

eil.com – the world’s best online store for rare, collectable and out of print Vinyl Records, CDs & Music memorabilia since 1987

Be the first to comment