The boom in digital streaming may generate profits for record labels and free content for consumers, but it spells disaster for today’s artists across the creative industries

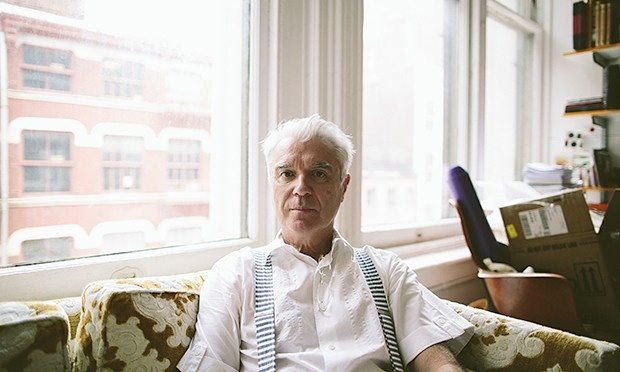

Awhile ago Thom Yorke and the rest of Radiohead got some attention when they pulled their recent record from Spotify. A number of other artists have also been in the news, publicly complaining about streaming music services (Black Keys, Aimee Mann and David Lowery of Camper van Beethoven and Cracker). Bob Dylan, Metallica and Pink Floyd were longtime Spotify holdouts – until recently. I’ve pulled as much of my catalogue from Spotify as I can. AC/DC, Garth Brooks and Led Zeppelin have never agreed to be on these services in the first place.

So, what’s the deal? What are these services, what do they do and why are these musicians complaining?

There are a number of ways to stream music online: Pandora is like a radio station that plays stuff you like but doesn’t take requests; YouTube plays individual songs that folks and corporations have uploaded and Spotify is a music library that plays whatever you want (if they have it), whenever you want it. Some of these services only work when you’re online, but some, like Spotify, allow you to download your playlist songs and carry them around. For many music listeners, the choice is obvious – why would you ever buy a CD or pay for a download when you can stream your favourite albums and artists either for free, or for a nominal monthly charge?

Not surprisingly, streaming looks to be the future of music consumption – it already is the future in Scandinavia, where Spotify (the largest streaming service) started, and in Spain. Other countries are following close behind. Spotify is the second largest source of digital music revenue for labels in Europe, according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI). Significantly, that’s income for labels, not artists. There are other streaming services, too – Deezer, Google Play, Apple and Jimmy Iovine of Interscope has one coming called Daisy – though my guess is that, as with most web-based businesses, only one will be left standing in the end. There aren’t two Facebooks or Amazons. Domination and monopoly is the name of the game in the web marketplace.

The amounts these services pay per stream is miniscule – their idea being that if enough people use the service those tiny grains of sand will pile up. Domination and ubiquity are therefore to be encouraged. We should readjust our values because in the web-based world we are told that monopoly is good for us. The major record labels usually siphon off most of this income, and then they dribble about 15-20% of what’s left down to their artists. Indie labels are often a lot fairer – sometimes sharing the income 50/50. Damon Krukowski (Galaxie 500, Damon & Naomi) has published abysmal data on payouts from Pandora and Spotify for his song “Tugboat” and Lowery even wrote a piece entitled “My Song Got Played on Pandora 1 Million Times and All I Got Was $16.89, Less Than What I Make from a Single T-shirt Sale!” For a band of four people that makes a 15% royalty from Spotify streams, it would take 236,549,020 streams for each person to earn a minimum wage of $15,080 (£9,435) a year. For perspective, Daft Punk‘s song of the summer, “Get Lucky”, reached 104,760,000 Spotify streams by the end of August: the two Daft Punk guys stand to make somewhere around $13,000 each. Not bad, but remember this is just one song from a lengthy recording that took a lot of time and money to develop. That won’t pay their bills if it’s their principal source of income. And what happens to the bands who don’t have massive international summer hits?

You can read the rest of this at the Guardian

[interaction id=”5623660d47771a9960f8d631″]

Be the first to comment