From inner groove loops to absurd backmasking, artists have long found ways to embed secret songs, cryptic writings and coded messages in their albums, if you can think of any others that aren’t in this article – let us know!

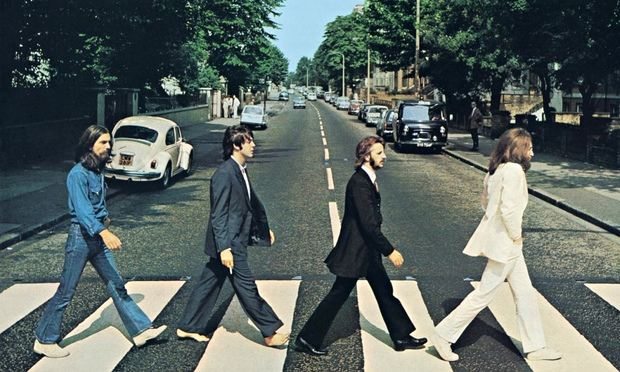

1. 1969: hidden tracks are invented, by accident, at Abbey Road

A tired teenager is to thank for the first ever secret track on an album. Now a Grammy award-winning movie soundtrack engineer, John Kurlander became a tape assistant at Abbey Road studios just after his O-levels: “I’d visited on a school trip, and was blown away, so I wrote to them – I couldn’t believe it when they took me.”

At 18, he was charged with putting together rough mixes of the Beatles’ Abbey Road medley (the 16-minute run of short songs from You Never Give Me Your Money to The End). The fourth song of this series, originally, was Paul McCartney’s Her Majesty. “I played it back to him at 2, 3am – very late, anyway. [Paul] said, ‘That’s all great, but take Her Majesty out now; it doesn’t work.’”

Studio rules meant any edited material had to be left at the end of the mix, so Kurlander left nearly 20 seconds before Her Majesty, and put the tape in Abbey Road’s tin of masters – crucially, not the basic cardboard box that they used for rough cuts. He added a note for mastering engineer, Malcolm Davies, saying why he had done this. But Davies, who had recently relocated to the Beatles’ Savile Row Apple studio, didn’t understand the note. “He couldn’t just come and find me and ask,” says Kurlander, “so he just went and cut the acetate.”

The final master was aired the next afternoon and the band had just started discussing the medley when Her Majesty kicked in and made them jump. “I remember the band looking at each other, then at me… and then going, ‘yeah!’” It makes him laugh how the track is over-analysed now. “It was just a happy accident. The Beatles loved happy accidents.”

2. 1970s and 80s: inner grooves, endless loops

If a turntable’s tonearm doesn’t have an automatic return function, the stylus will run around a record’s inner groove, silently, for ever. Music can be recorded into this space though, and experimental musicians have recorded passages to be repeated continuously.

The Beatles kicked things off in 1967, adding a whistle and a sped-up Paul McCartney to the end of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, while six months later, the Who’s The Who Sell Out ended with heavily distorted vocals chanting “Track Records” (the name of their label).

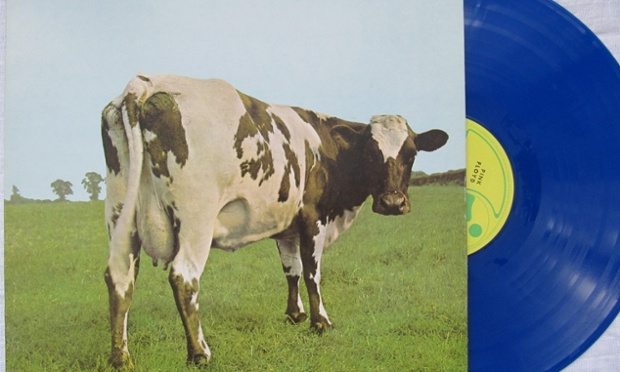

The 70s and 80s, however, were the boom years. Aficionados include Pink Floyd (a never-ending dripping tap on 1970’s Atom Heart Mother); Brian Eno (chirping crickets on 1976’s Taking Tiger Mountain – By Strategy); Heaven 17 (the line “for a very long time”, from the song We’re Going To Live for a Very Long Time, on 1981’s Penthouse and Pavement, going on for… a very long time); and Abba (incessant applause concluding 1980’s Super Trouper).

3. 1970s: a humble record-cutter popularises the “run-off groove” message

George “Porky” Peckham cut records for the Beatles, Genesis and Led Zeppelin before setting up his own business in London’s West End, attracting punk and indie bands with cash-price deals. When he finished a job, he’d “sign” his nickname into the deadwax between the music and the label – either Pecko, Pecko Duck, Porky, or his most famous inscription, “A Porky Prime Cut” – and add dryly humorous phrases. Some etchings were surreal (“This is rather nice, isn’t it?” and “Mange l’escargot… Mmm!” on the A and B sides of the Pretenders’ Brass in Pocket); some were critical (“You’ll Never Work Again” on the Fall’s 1980 albumTotale’s Turns).

Musician Terry Edwards – now part of PJ Harvey’s Somerset House band, but also author of the 33 1/3 book on Madness’ One Step Beyond, featuring an appendix on run-off grooves – worked with Porky, who is now retired, many times. “He was the best record-cutter around, very down to earth. He was the kind of bloke you’d book the morning cutting session with and have a pint with him at lunchtime – you wouldn’t book the afternoon one because that’d be after his pint!” Porky also encouraged bands to scratch in their own messages. “To fans, they felt like little messages given only to people who were into alternative music, although in reality bands went to him because he was cheap.”

4. Mid 80s: bands run with the run‑off groove

Bands often liked to choose run-off groove messages themselves. The Smiths’ featured Morrissey’s wit – “Home Is Where the Art Is” was scrawled on 1985’s Shakespeare’s Sister, while “Are You Loathsome Tonight?” and “Tomb It May Concern” appeared on 1986’s Ask.

Joy Division’s 1980 album Closer included the inscription “Old Blue”, a reference to Tony Wilson trying to get singer Ian Curtis to sing like Sinatra, but their final four-sided compilation, Still, included a darker memorial.

“Ian was always adamant that we should do run-off grooves if we could,” remembers bassist Peter Hook. “He saw them like a little game, to get obsessed with, to keep the myth and magic going.” Along with manager Rob Gretton, Hook oversaw those final run-off grooves. Still’s A-side bore the words “The Chicken Won’t Stop”, followed by two sides of chicken feet etchings, then the words “The Chicken Stops Here”. These words reference the final scene of Werner Herzog’s film Stroszek, in which a chicken dances in a coin-operated attraction as the protagonist apparently kills himself off-screen. It was the last film Curtis watched before he committed suicide.

5. 1980s: backmasking reaches its peak

Backmasking is the recording of music or lyrics in reverse, often resulting in eerie, mangled passages of sound. Some practitioners were accused of Satanism by Christian pressure groups and conspiracy theorists, partly thanks to the popularity of occultist Aleister Crowley, who suggested in a 1913 book that would-be magicians train by listening “to phonograph records reversed”. Messages started to “be found” that weren’t there, and in 1990 Judas Priest were taken to court, accused of recording a message (that didn’t exist) that had provoked a teenager to commit suicide.

ELO’s 1983 album Secret Messages is full of absurd, backmasked statements, such as Jeff Lynne saying “you’re playing me backwards”, played backwards.

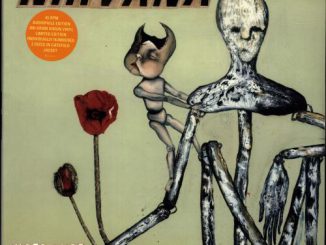

6. 1990s: non-vinyl formats prompt a hidden-track boom

Cassettes were the most popular audio format in the early 90s, and tracks could be hidden neatly, and invisibly, at the end of the second side. Bands often used this space as a showcase for their less mainstream tendencies. Nirvana’sNevermind finished with the six-minute noise of Endless Nameless, and the Lemonheads’ Come on Feel the Lemonheads concluded with three spaced-out guitar jams.

CDs allowed the inclusion of a song in the “pregap” – the space before track one, only accessible by pressing rewind (interestingly, this still cannot be read by computers while uploading tracks today). Ash put their debut single, Jack Names the Planets, in this space on their album 1977; Super Furry Animals put pregap tracks on 1997’s Guerrilla and the 1998 compilation Out Spaced; and Unkle, the James Lavelle/DJ Shadow outfit, inserted a track teeming with samples of their influences on 1998’s influential Psyence Fiction – it would have been difficult to get clearance to use all these pieces.

Some people still use the pregap. Arcade Fire’s latest album, Reflektor, includes a 10-minute hidden instrumental, played in reverse.

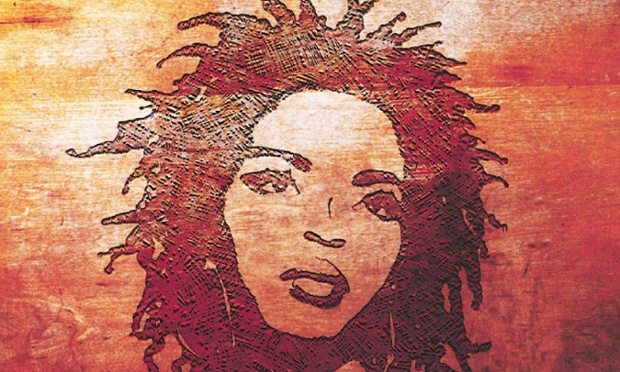

7. 1999: a hidden track gets nominated for a Grammy

Lauryn Hill’s cover of Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons’ Can’t Take My Eyes Off You, recorded for the soundtrack of the 1997 thriller Conspiracy Theory, was a hidden track on her debut album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. It missed out to Celine Dion’s My Heart Will Go On for 1999’s best female pop vocal Grammy.

8. Today: Jack White goes ultra

A few record presses still exist in the UK – including newer, small companies such as Curved Pressings and Vinyl Carvers in London – but most alternative records get pressed in the Czech Republic. If you want to get secret tracks or locked grooves on your record, it helps to own your own label.

Enter Jack White. The ultra edition of his 2014 album, Lazaretto, released on his own label, Third Man, included hidden tracks recorded at 45 and 78rpm, secret tracks under the centre labels, different grooves on Just One Drink (allowing you to hear either an acoustic or electro intro, depending on where the needle is dropped), and side A plays from the inside out, with a reverse groove.

“All this stuff is outwardly for the faithful, as another means of communication, but it’s also, crucially, another means of differentiation,” says Travis Elborough,author of The Long-Player Goodbye, a history of the vinyl record. “It’s not just about the physicality of the record in the age of the internet either, but doing something that makes you stand out.” It says much that Jack White’s record lists its “hidden content” too – gone is the magic that lurks quietly before the needle brings the noise.

Thanks to the Guardian for this article

Be the first to comment