Can the creaking machinery of the few remaining record pressing plants cope?

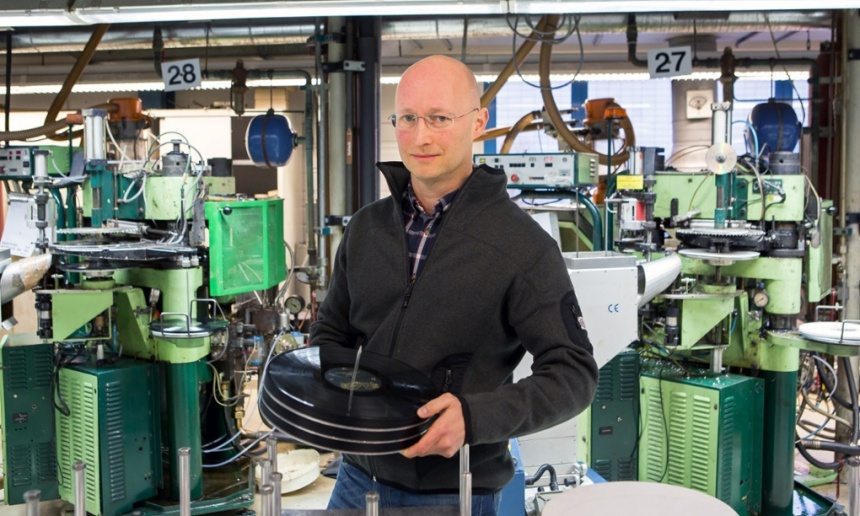

On an industrial estate in Röbel, 90 miles north of Berlin, the vinyl presses at the Optimal factory were grinding and pumping away. They made a percussive racket – regular clunks, wheezes, and hisses, underlain by a droning hum – and created a distinct aroma, sharp and metallic, suggestive of steam engines and old cars: not instantly recognisable to a British visitor like me, perhaps, but the singular smell of things being made. My guide to the Optimal plant was its operations director, Peter Runge. Together, we watched copies of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ Live From KCRW tumble from one of the machines. Across a narrow aisle, a press dedicated to seven-inch records was spitting out copies of The Boy From New York City, a 1964 single by the Ad Libs, a soul group from Bayonne, New Jersey. A few yards away sat fresh stock of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. Next to those was a growing pile of the album Clandestine by the Swedish death metal band Entombed, being pressed on purple vinyl. Beside each machine, bins were collecting surplus plastic shorn off the edges of each disc, to be fed back into the production process.

“Instant recycling!” said Runge, who stared at the factory’s operations through rimless glasses. He grew up, he told me, in Rostock, in the old German Democratic Republic. When he was 19, he applied for an ausreiseantrag – an East German exit visa, the same day as the East German premier Erich Honecker visited West Berlin. This modest act of subversion led to an appointment with the Stasi, and he was barred from going to university. So he got a job in the university’s workshop, helping to build electronic prototypes, where he gained a practical understanding of engineering. When the Berlin Wall fell, two years later, he belatedly became an undergraduate at the same institution, and eventually earned a PhD in industrial maintenance. He joined Optimal Media in 1997, was put in charge of “process optimisation and re-engineering” and given the job of setting up a production planning system. Now 46, he oversees the manufacture of DVDs, CDs and books, but the task in which he takes the most pleasure is supervising the production of vinyl records, in what he and his colleagues claim is Europe’s biggest pressing plant. Their clients are split between the major record companies – who have trusted Optimal with the work of such titans as the Beatles, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin and David Bowie – and the independent companies who kept the vinyl format alive through the 1990s and early 2000s while the rest of a terrified music industry embraced digital technology. Optimal’s machines run 24 hours day, for most of the year, and production capacity has to be booked up to a year in advance. And every hiss and wheeze of the company’s machines attests to a story that, 20 or so years ago, would have seemed unthinkable: the renaissance of the vinyl record.

In the first half of 2014, officially registered sales of vinyl in the US stood at around 4m, confirming an increase of more than 40% compared to the same period in 2013. In the UK, this year’s accredited sales will come in at around 1.2m, more than 50% up on last year. That may represent a tiny fraction of the industry’s estimated sales of recorded music, but still, a means of listening to music essentially invented in the 19th century and long since presumed to be dead is growing at speed, and the presses at Optimal – along with similar facilities smattered across the UK, mainland Europe, the US and beyond – are set to grind and pump on, into the future.

“Isn’t it strange?” Runge mused. “I’m an automation engineer. I never thought I’d be dealing with vinyl. It’s unexpected. But it’s also unexpectable.” He shouted this over the din of the machinery. Each press sat in a space not much more than four metres square. Two circular paper labels were mechanically plucked from one end, while tiny vinyl pellets were sucked into a steam-driven heating process. The result was a hunk of plastic with the circumference of a beer mat, heated to 130C, to which the labels were attached, while 50 tonnes of hydraulic pressure squashed and spread it into a disc. Metal stampers pressed against either side, and it was quickly cooled to 40C. With another clunk, the finished product was dropped on to a spindle, ready to be inserted in its sleeve. The whole cycle had taken 27 seconds. Each day, the factory makes somewhere between 50,000 and 55,000 records.

Hanging over everything Runge showed me was an awkward question. While demand for records is increasing year by year, Optimal’s stock of machinery is old, and getting older. New presses are unaffordable, unless the big companies were to invest, but vinyl is still too small a sector of the market for them to be convinced. The kind of painstaking maintenance and technical ingenuity one might think of as the Cadillacs-in-Cuba model keep the industry going. But for how long?

When former music journalist Michael Haentjes started the independent German label Edel in 1986, he relied on other companies to press his records. “They usually didn’t get him the best delivery times,” Runge said. “They put him to the end of the queue. So by the 90s he said, ‘No – I’m sick of it. I’ll build my own plant.’” Thanks to economic policies aimed at assisting reunification, Haentjes, who was from Hamburg, decided to locate his new factory on an industrial estate in Röbel, an unremarkable East German town in the Mecklenburg Lake District (20 minutes’ drive away is Waren, a spa resort where Soviet nuclear missiles were located as recently as 1988).

At that point, it looked as though vinyl would soon become obsolete. Records had first been superseded by cassettes, which were portable (they had become indispensable with the introduction of the personal stereo) but chronically unreliable. With the arrival of the compact disc in 1983 – introduced to consumers with the lure of cleaner sound and the entirely specious promise of indestructibility – old-style records looked to be finished. At a music industry conference held in Athens in 1981, executives had responded to a demonstration of the CD by chanting “The truth is in the groove!” But just over 10 years later, 70.5m CDs were bought in the UK, compared with a miserable 6.2m records.

In that context, Haentjes’s decision to begin pressing records looked ludicrously sentimental. The company bought and installed its first vinyl presses in 1995, to service demand from independent companies producing dance music. DJs still specialised in the art of playing and mixing 12-inch records. Moreover, if a dance single was to be a hit, its progress towards success would often start with its circulation as a limited-edition “white label” record, usually pressed up in the mere hundreds.

These records often sat at the cutting edge of musical fashion, but at the same time, Optimal’s vinyl production lines were redolent of a world that had recently disappeared from view. Then as now, many of its staff – from those who pressed and packed the records to its senior management – were former East German nationals, with vivid memories of life under communism. For them, the advent of the CD had coincided with the last phase of the cold war, so that those little silver discs became a byword for western aspiration, and the kind of technological progress the eastern bloc could not get near (in the GDR, Peter Runge told me, the authorities had approved the release of just three CDs, all of which were produced in the former Czechoslovakia).

Most of the pressing machines Optimal acquired had come from decommissioned factories, in the decade-long fire sale that followed the fall of the Soviet Union. “When you buy a press, it’s usually inoperative,” said Runge, as we passed giant piles of freshly printed sleeve art for Kraftwerk albums. “A lot of machines won’t work any more, because something is broken, the electronics are missing, or something like that. And then you have to find all the spare parts, or make spare parts – because the company who made the presses no longer exists. Then you have to strip the machine down, and redo all the hydraulics and the electronics.” Engineers from the old East Germany, he told me, tend to be very good at this. “They always know how to improvise.”

In the late 1990s, six machines were used for production, while the rest were kept in storage, for spares. But at this point, after years of steady decline, the international market for new vinyl was plummeting. By 2001, the dance music world was increasingly embracing CDs, laptops and MP3s – the latter could instantly be circulated around the world, bypassing the old ritual of white-label pressings altogether. Now, Runge began discussions with Optimal’s senior staff about whether they should leave records behind. “There were a lot of meetings,” he remembered. “We asked ourselves: how long will we make records? Should we continue to manufacture vinyl? But then we decided that it had to be part of our service.”

In 2007, Optimal was presented with the chance to buy 15 more Swedish presses from Audio Services Limited (ASL), a company based in a backstreet in east London that was facing liquidation. “We had to decide whether to get the machines and continue doing this on a larger scale, or leave the business small, like it was.” At the very least, they thought, some of the new machines could be used for the ASL business that would come as part of the deal, while others would be a much-needed source of spares. “So we decided, ‘Get the machines,’” said Runge. He cracked an understated smile. “And that was a good decision, I think.”

Runge made regular trips to the plant at Orsman Road, N1, where he inspected what was on offer – not just presses, but an archive of the metallic master copies of stampers used to make thousands of different records, by artists including Simon & Garfunkel and the Manic Street Preachers, all of which could conceivably be put back into production. And he immersed himself in negotiations with the factory’s owners.

“We bought everything,” he told me. “We emptied the building.” The presses were loaded on to two trucks, with the whole of ASL’s archive on hundreds of pallets, and ferried across the North Sea to Röbel.

The gamble was worth taking. During the 2000s, buyers had increasingly expressed a desire to hear music rendered as perfectly as possible. New vinyl-only labels had started to produce albums intended to capitalise on this interest, and on rock music’s inbuilt nostalgia. A new format had been created – 180g records as opposed to the standard weight of 120g – and to counter the digital streaming culture, these were records you’d want to own, presented in luxuriant box sets, complete with hardback books and exact-replica artwork. In 2008, vinyl had been given its own annual celebration: Record Store Day, on the third Saturday in April, when record companies would create thousands of limited-edition records coveted by collectors. Meanwhile, astute independent companies such as Rough Trade, Domino and Bella Union had begun accompanying their records with exclusive download cards, so that anyone buying them could also access digital versions of the music – and thus, if they wished, not just put their new music on phones and iPods, but keep their records pristine.

“The majors hopped on the wagon,” said Julia Völkel, 32, Optimal’s senior sales manager, another former East German, who joined the company in 2000. “And they were very interested in doing box sets. They found out that catalogue releases sold very well as gifts …”

“… And nowadays,” said Runge, “we’re 100% full. We’re running, always, on the brink of maximum capacity.”

In a meeting room near the factory, Runge projected a graph showing average monthly output between 1999 and 2014. When the line got to 2011, it suddenly shot upwards: in only three years, production more than doubled, and the risk Optimal had taken in 2007 paid off. By 2013, the company had 27 active presses, manufacturing records around the clock. This year (2015), with the addition of two machines that have been brought out of storage, the company says it will press 18m records.

In October 2010, on a Sunday evening, 14 people gathered in the wood-panelled upstairs room of the Hanbury Arms, on Linton Street in Islington, north London. Two of those present paid an entrance fee of £5; the rest were invited guests. They had come to listen to a vinyl copy of Abbey Road, the Beatles’ last album. The event was the first of a series called Classic Album Sundays, and the idea was simple enough: a small crowd would come together to spend a couple of hours eating, drinking and talking, before they took their seats, snapped into silence, and listened to both sides of an album played on hair-raisingly expensive equipment.

A similar concept had already been tried in Liverpool, under the title Living To Music, where, in August, a DJ and producer called Greg Wilson had gathered people to listen to a vinyl copy of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon. He invited other people to do the same thing at the same time – 9pm on a Sunday – and then share their experience online. The idea reflected a key factor in vinyl’s revival: Spotify and iTunes propagated a mode of listening whereby people could flick between tracks on a whim and, for the most part, shut out others with the aid of headphones; vinyl represented the option of really listening to a whole record – often in company.

The London event was organised by an American named Colleen Murphy, who listened to the whole of Abbey Road lying on the floor. It was reviewed by the music magazine the Word, in which Kate Mossman described 40 minutes when “eyes are focused in the middle distance, unseeing, as though every sense is shutting down in service of the ears”, and a picture captured the attendees lost in music, stroking their chins, covering their eyes, or horizontal. In early 2012, Classic Album Sundays was the subject of an item on the BBC Breakfast TV programme. Ever since, most of Murphy’s events have been sell-outs, and there are now offshoots in Glasgow, New York, Oslo and Portland, Maine.

Murphy has lived in Britain since 1999. She DJs as under the name Cosmo, produces and remixes music, and runs a vinyl‑only label called Bitches Brew. At New York University, she became the programme director of the renowned college radio station WNYU – and in the early 1990s, she began an enduring friendship with David Mancuso, who pioneered parties in Manhattan known as the Loft, where he played music through ambitious audio set-ups, only ever on vinyl.

You can read the rest f this fascinating article on the Guardian website

Be sure to check eil.com for all your vinyl needs

Be the first to comment