Rock orthodoxy reveres them, but the truth is that classic albums don’t have to be classic all the way through. All you need is enough great songs to make a statement – as these five examples prove

A thought occurred while listening to Dr Dre’s landmark album The Chronic, which starts out like the most fantastic party but somehow devolves into a grim trudge towards the reprehensible final track Bitches Ain’t Shit. It completely fails to reach the finish line and yet it remains one of hip-hop’s defining albums, thus raising the question: how patchy can an album be and still be ranked in the pantheon of classics?

Anybody who, at a curious age, has investigated a list of the best albums ever will have found some they dislike. That is inevitable. A much chewier proposition is a record with as many troughs as peaks. Here are five albums that regularly appear on those best-ever lists despite their (in my subjective opinion) inconsistency. This isn’t about masterpieces flawed by a single track, a phenomenon the writer Andrew Mueller calls “Jazz Police Syndrome” after the solitary clanger on Leonard Cohen’s I’m Your Man. And it excludes double albums, which are meant to be ragged sprawls. A flawless single-disc re-edit of the White Album wouldn’t be the White Album. It would be like Moby-Dick without the long disquisitions on the uses of whale blubber. The aim is certainly not to slaughter sacred cows, which has become as much a cliche as the canon itself. (The nature of the canon, which is still dominated by male rock artists from the 60s and 70s, is a whole other issue.) The question is how these albums manage to be great despite their flaws.

It’s about asking what makes an inconsistent album a classic. How much of it needs to be brilliant? Half? One-third, even? If the bad, or at least mediocre, outweighs the good but the good is astonishingly, inspirationally, career-definingly great, is that enough? Can highlights be so exceptional that they become the rising tide that lifts all boats rather than mountains surrounded by hillocks? Do contemporary impact and subsequent influence render a fistful of duds irrelevant? Ultimately, is consistency overrated? If a classic novel’s reputation can survive implausible plotting or underdeveloped characters, then an album can be far more than the sum of its sometimes shonky parts.

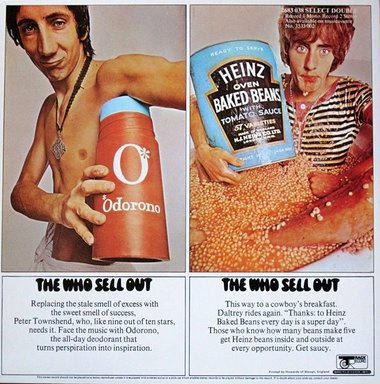

The Who

Sell Out (1967)

Inspired by their own dalliance with shilling for The Man, the Who were way ahead of the game in satirising the idea of rock’n’roll as a consumer product. Sell Out’s ersatz commercials and pirate-radio jingles must have been quite a revelation in 1967, but the concept originated as a desperate attempt to paper over the songwriting cracks. Under pressure from manager Chris Stamp to record the Who’s third album in a hurry, Pete Townshend “needed an idea that would transform what I regarded as a weak collection of occasionally cheesy songs into something with teeth”, he told one interviewer. Well, he said it.

Rolling Stone retrospectively called Sell Out “the most successful concept album ever”, which is bizarre considering that most of the songs bear no relation to the jingles: the first, the on-the-nose psychedelic escapism ofArmenia City in the Sky, wasn’t even written by a member of the band. Like Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Sell Out is only pretending to be a concept album. Even the Who get fed up with the idea by the end, wrapping up with the mini-opera Rael 1 & 2. Consistency is not Sell Out’s strong point.

Nor is the sheer power that was the Who’s main attraction on stage. Notwithstanding lovely highlights Tattoo, Our Love Was and I Can’t Reach You, Sell Out sounds studio-bound, fussy and thin, fattened up with gimmicks and gewgaws. It dabbles too long in psychedelia, for which, like the Rolling Stones, the Who had little affinity and which they would quickly leave behind. I Can See for Miles is so hungry and explosive that it sounds as if it’s trying to break out of the album and find a better, heavier one where it would have some suitable company and not have to hang around with whimsical tosh such as John Entwistle’s Silas Stingy. It’s the tentpole that keeps the whole rickety, if charming, structure upright.

You could make a similar argument about Tommy, Quadrophenia and Who’s Next (which doesn’t even have a concept to hide behind), but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

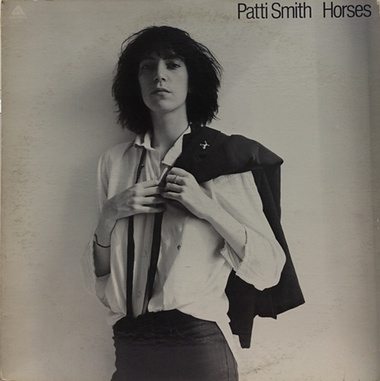

Patti Smith

Horses (1975)

Horses is a lightning bolt of a record. It crunched together the highbrow and lowbrow ends of postwar American pop culture in the shape of an utterly fearless woman who was at once a shamanic beat poet and a garage-rock dynamo. In the memoirs of musicians, especially female ones, it recurs as a catalyst for transformation and liberation. “Up until now, girls have been so controlled and restrained. Patti Smith is abandoned,” writes Viv Albertine in Clothes Music Boys. “Her record translates into sound parts of myself that I could not access, could not verbalise, could not visualise, until this moment.” Michael Stipe said it “tore my limbs off and put them back on in a whole different order”.

It achieves this, to be honest, in its first six minutes. Gloriatells you everything you need to know about who Patti Smith is and what she’s here to do. The three-part Land tells you again, only at 50% longer, and that’s fantastic, too. Free Money is a great palpitating rock song. Birdland is Smith at her most poetic, soaring skywards on an updraft of words. Those four songs make Horses a landmark. Not the straightforward rock ofKimberley or the dirgey Break It Up. Not the muted anti-climax of Elegie. Certainly not the synthetic reggae of Redondo Beach, which is one of the all-time track-two buzzkills. You don’t change lives with songs like that. But more than any other record, Horses proves that a giant personality and a new way of apprehending the world can make an album’s strike rate irrelevant.

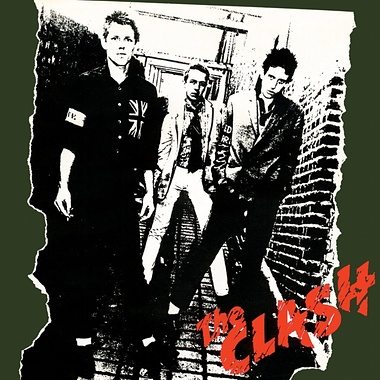

The Clash

The Clash (1977)

Consensus opinion says that Give ’Em Enough Rope was a misfire, Sandinista! was heroically ambitious but too long and we don’t talk about Cut the Crap. The Clash’s debut is the origin myth, the noisy arrival of a truly great band, and you can tell what it must have meant in 1977 when the NME’s Tony Parsons called it “some of the most exciting rock’n’roll in contemporary music” and said that the Clash chronicled “what it’s like to be young in the Stinking 70s better than any other band”. But, some distance from the Stinking 70s, its weaknesses are more apparent.

The Clash opens with four agenda-setting shocks to the system – Janie Jones, Remote Control, I’m So Bored With the USA and White Riot – and contains one of the band’s bravest experiments, their cover of Junior Murvin’s Police and Thieves. The rest is mostly forgettable and formulaic: a string of songs about boredom and frustration that eventually become boring and frustrating, bottoming out with the hopelessly underachieving Garageland. The songwriting and the imagination that made the Clash essential weren’t quite there yet.

Unlike the Ramones, the Clash didn’t turn blunt-force repetition into a gonzo aesthetic. Their real achievement, just around the corner, was to make punk rock seem bigger and broader than anyone else did: White Man in Hammersmith Palaisalone makes the debut seem gauche and narrow. That song appears on the US version of this album, which replaces four weak tracks with knockout singles and is the strongest possible argument against the original British version. The Clash’s debut is a snapshot of a galvanising moment in British music but it took them until London Calling to produce the full picture.

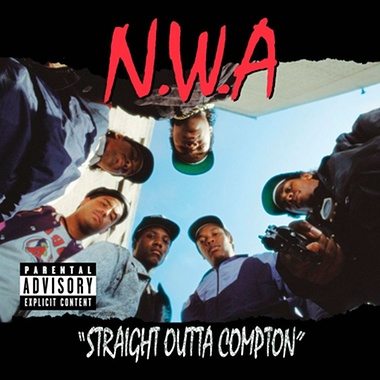

NWA

Straight Outta Compton (1988)

You don’t need last year’s lionising NWA biopic to tell you that gangsta rap’s Big Bang revolutionised hip-hop. But with what, exactly? The title track’s mix of conflicted pride and taunting bravado, powered by a breakbeat with the crushing force of one of the LAPD’s infamous battering rams. Fuck Tha Police, an audaciously belligerent middle-finger protest song less concerned with changing the system than with being left the hell alone. Gangsta Gangsta’s joltingly amoral manual for How to Be a Gangsta Rapper. The first three tracks, basically.

Straight Outta Compton is a milestone because NWA’s scowling worldview – anger without a message, partying without levity, realism verging on nihilism – made no concessions and no promises. These were voices the music world hadn’t heard before, not even in hip-hop. They were, as Chuck D has said, the Sex Pistols to Public Enemy’s the Clash. But after the opening salvo, NWA spend most of the album repeating themselves, often stiffly, over the kind of basic funk samples and sparse, Run-DMC-style beats that were already old hat in 1988. The unexpectedly benign self-help party jam of Express Yourself is a lot of fun, though not the kind of thing musical revolutions are made of.

Lyrical inspiration runs perilously low during a second half padded out with rote braggadocio, fearful adolescent misogyny and dubious claims: when MC Ren boasts, “We’re positive and they’re on a negative type,” on Something Like That, you wonder if he has listened to the rest of the album. For some reason, the last track is a throwback showcase for Arabian Prince, the founding member so minor that he doesn’t even appear in the movie. Dr Dre’s solo albums The Chronic and 2001 also tail off badly and get away with it. Dre has always known that if you frontload an album with groundbreaking brilliance, then you don’t have to worry about the conclusion.

See more at the Guardian

Did the Guardian miss something? Which ‘classic album’ do you think is fundamentally flawed?

Find a huge range of rare vinyl, CDs, music memorabilia and more at eil.com

Kinda disagree re The Clash 1st Album. Yeah, the rest is mostly forgettable and formulaic: a string of songs about boredom and frustration, but it’s not the content of the songs that is important, but the power. When you take “48 Hours” at 1:34, “Career Opportunities” at 1:51 and “Protex Blue” at 1:45 in length, It’s the sheer energy and force of the band that counts. As a teenager in ’77, I had never before been blown away by such short, sharp songs, and, in my eyes at least, every one is a gem.